Über den Blog

Wir geben Einblicke in die Versicherungswelt - von A wie Altersvorsorge bis Z wie Zinszusatzreserve.

Meistgelesene Artikel

Kontakt

Sie haben eine Frage oder Anregungen zum BdV-Blog? Dann nehmen Sie gerne Kontakt zu uns auf!

Neueste Kommentare

Tag Cloud

Kontakt | Impressum | Über den Blog | RSS-Feeds | Suche | Autoren | Rechtliche Hinweise und Kommentarrichtlinien | Datenschutz | Cookie-Einstellungen

Reduction of „Annuity Factor“ of private pensions: inevitable development?

Reduction of „Annuity Factor“ of private pensions: inevitable development?

The fundamental question of this article is, whether the ongoing reductions of “annuity factors” of private pensions offered by life-insurers are really an inevitable development? Examples of researches taken from the German PPP market, guiding questions for prudential and business of conduct supervision and their consequences for consumers are highlighted.

First it must be elucidated, what is an “annuity factor” or an “annuity rate” (“Rentenfaktor”)? Per definition it is the amount of a life-long monthly annuity per 10.000 Euro of accrued capital at the beginning of the pay-out phase.

Example: if the annuity factor is fixed by 30, and the accrued capital amounts to 50.000 Euro, than 30 times 5 equals 150 Euro of life-long annuity. The exact calculation of the “annuity factor” is made by each life-insurer which mainly takes into consideration the estimated average life-expectancy of its portfolio of PPP contracts, the expected developments of interested rates, and some additional prudential risk “reserves” as well with regard to biometric risks as to capital market risks stipulated by the supervisory authorities.

Usually the annuity factor is guaranteed from the beginning of the pay-out phase on, but in the past before the low interest rate phase it was already guaranteed from contract conclusion on by many life-insurers. At least following to the German law even in this case – under certain conditions and testified by a fiduciary – it was nevertheless possible to change the annuity factor.

The examples of the reduction of the annuity factor by life-insurers are based on a contribution phase of 35 years with the start of the pay-out phase at age 67, all taken from a study of the German PPP market in 2022:1

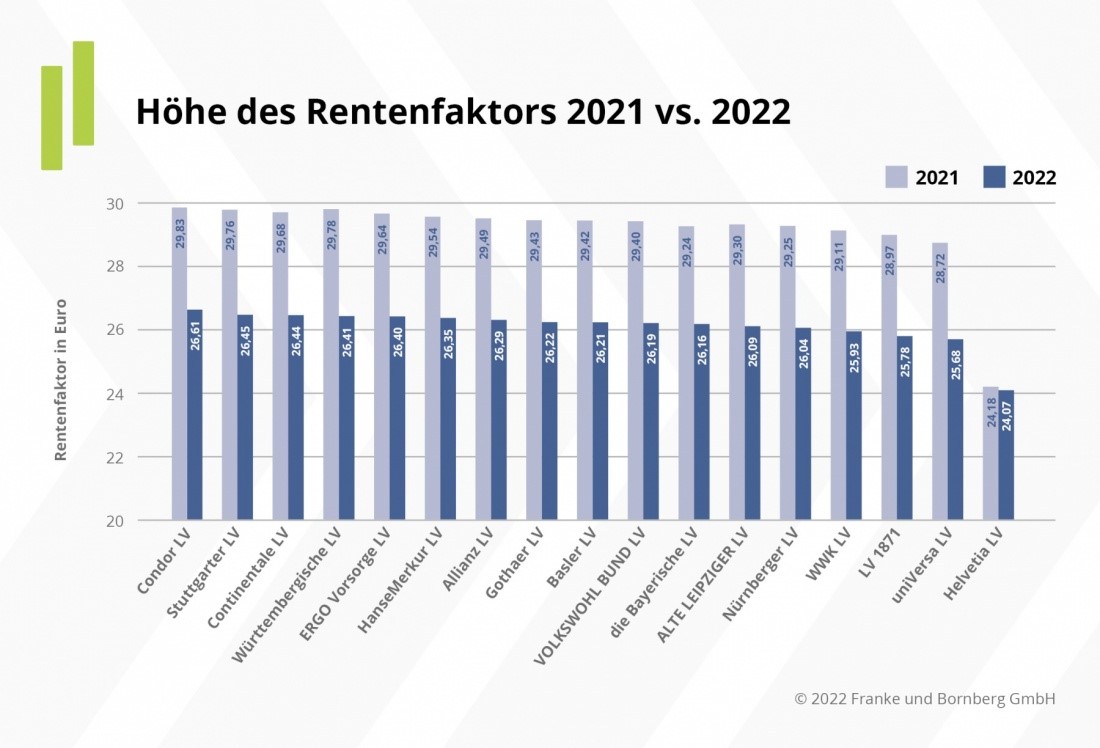

The first table shows the reduction of the “annuity factor” from 2021 to 2022 with the amount guaranteed at beginning of decumulation phase:

The table shows that there is an average reduction of the annuity factor from about 29 (in 2021) to about 26 (in 2022), so more than 10% in just one year.

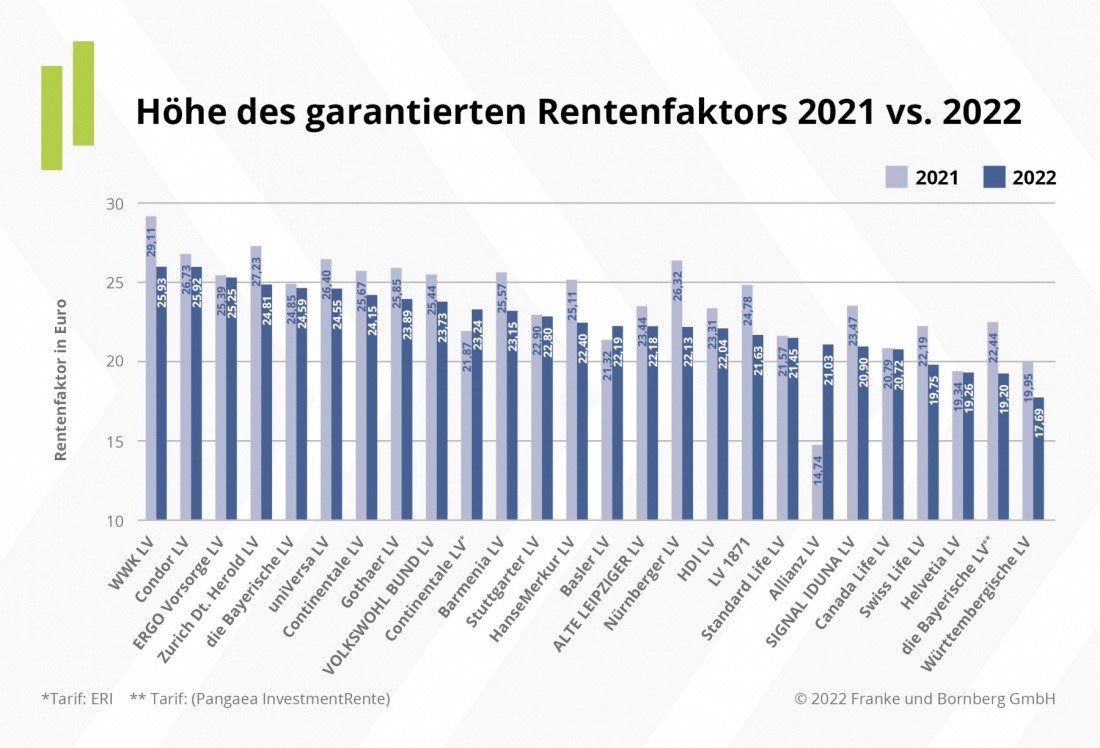

The second table shows the reduction of the “annuity factor” from 2021 to 2022 with the amount guaranteed from contract conclusion on:

This table clearly shows, too, that there is an average reduction of the annuity factor from about 25 (in 2021) to 22 (in 2022). There were only two exceptions, especially the Allianz which nearly doubled its “annuity factor”, but it was by far the lowest in the market before. The absolute amounts of the “annuity factors” are lower, so the reductions are lower, a fact related to the much longer duration of the guarantee which is given.

These figures examplify that the reductions of the “annuity factor” are empirically proven. So, what may be the consequences of this fact as well for retail investors and policyholders as for supervisory authorities? Therefore some guiding questions for the prudential and conduct of business supervision are useful from our perspective:

- Life-expectancy: in order to evaluate, if the calculation of the life-expectancy can be considered as “fair”, three different calculations should be compared:

- Life-expectancy of the general population (cohorts following to the date of birth),

- Mortality tables of actuaries,

- Life-expectancy of policyholders calculated by life-insurers.

The differences can be rather strong, for the figures for the general population and the mortality tables calculated by the actuaries are judicially not binding for the calculation of the life-insurers related to their particular portfolio of PPP contracts. Very often it is stated by life-insurers that their assumptions of life-expectancy are much higher in comparison to the average population, because PPP policyholders are in better health. But is this really the case?

For Germany the insurers themselves published figures that the average life-expectancy of 90 years for men is only achieved for boys born in 2020. Boys born in 1960 have an average life-expectancy only of 76 years.2 In order to compare, one just has to make a calculation - by using the annuity factor - how many years it will take that the total of the pay-outs will reach the “break-even” point of the contributions made before.

- Redistribution of benefits during the decumulation phase to individual policyholders: Following to the necessary “prudential” calculation of longevity it is possible that during the decumulation phase the actual development of mortality might be different as expected. If mortality is higher, for example due to the pandemic, biometric risks gains may emerge, because pensions do not need to be paid as long as calculated. In the same way additional gains from capital market investments by life-insurers may occur, if interest rates increase stronger than anticipated, like it was the case in 2022.

In consequence the “smoothing mechanisms” should be applied to the policyholders already receiving pay-outs as well. In both cases supervisory authorities ought to follow closely that there is a fair balance of the necessary “collective” capital reserves of the life-insurers and the timely increase of pay-outs to the pensioneers.

- Quality of “advice” given by intermediaries: in contrast to the two first questions which are primarily related to the prudential supervision the third issue is related to the supervision of conduct of business of life-insurers.

From the perspective as consumers, annuities are per se complex products, because they combine a long-term saving or investment process with a biometric risk coverage. Longevity is by definition uncertain and can be considered as a “bet” on the individual life-expectancy, which mainly depends on the individual state of health. Therefore it has to be questioned: will this crucial context really be explained in detail by a tied agent or broker paid via commissions?

Additionally must be asked: will the substantial difference between a “annuity factor” guaranteed from contract conclusion on or from the beginning of the pay-out phase on really be explained under the conditions of a “sale without advice” (following to IDD)?

But not only pension products including annuities or draw down plans are complex ones, but the entire constellation of retirement income is a very complex issue. What is the best combination of the various pay-out options (life-long annuity, draw-down plan or lump sum) for the individual retiree?

To give an example: we advocate that annuities should only cover the ongoing essential minimum expenses (like food, residence, maybe nowadays telecommunication, but not i.e. travels or furniture). Of course each individual must decide, where is the threshold. But it seems to be obvious that the higher the income, the more flexibility is needed.

This is all the more necessary as usually, after the beginning of the pay-out phase in case of death of the policyholder the remaining accrued capital belongs to the insurer. This effect can somewhat be “softened” by including a clause of “guaranteed pension period ” (usually valid for ten years after the beginning of the pay-out phase another person fixed in the contract may receive ongoing pension pay-outs for the rest of this period).

In consequence flexibility implies free choice of pension products by the long-term saver, for a consumer has to be enabled to take a “well-informed decision” following to IDD and MIFID II. This can only be realized – by considering the general conditions of complex pension products and complex constellations of retirement provision - by a fully “independent advice”. That is why we support EIOPA’s proposal to integrate the concept of “independent advice” as part of MIFID II into IDD outlined in EIOPA’s Report on “Retail Investor Protection” of April 20223.

Taking into consideration these guiding questions we conclude that the reduction of annuity factors of life-long pension products is not an inevitable “destiny”. Supervisory authorities must strictly analyse the fundamental assumptions of their calculations, if life-insurers continue to do so, because they are the only institutions – apart law courts – having the legal permission and therefore the obligation to exercise control. Additionally consumers must be enabled to have the awareness that annuities are not the only option for their long-term retirement income and that in most cases a combination of different options seems to be the best way to ensure as well fundamental stability as necessary flexibility.

1 Was bedeutet der Rentenfaktor und wie hoch ist er? Website: https://www.franke-bornberg.de/blog/was-bedeutet-rentenfaktor-wie-hoch-2021-2022

2 GDV: Die Positionen der deutschen Versicherer 2021, S. 18/19 (Demografie).

3 EIOPA publishes advice on Retail Investor Protection, Press Release of 29 April 2022. EIOPA-Website: https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/media/news/eiopa-publishes-advice-retail-investor-protection

https://www.franke-bornberg.de/blog/wie-hoch-rentenfaktor-check-2023